Whether you are a Come’yuh or a Bin’yuh, there is magic to be found on Daufuski Island.

by Susan Frampton

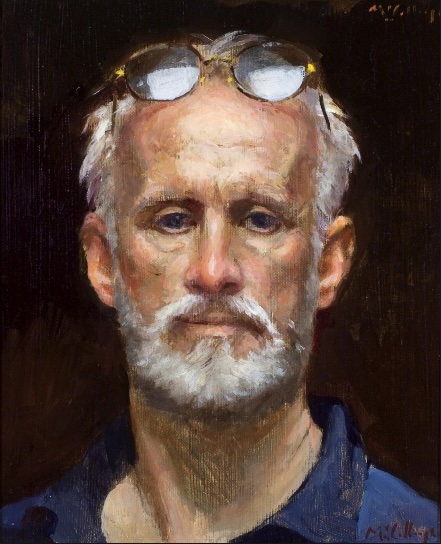

Photography by J. Lachenman

Over 1,000 barrier islands are strewn along the southeastern coastline, stretching from North Carolina’s Cape Fear to northern Florida. Some are small and uninhabited, while others have become integral parts of mainland communities. Among them, Daufuski Island is a unique jewel set in the heart of the Lowcountry. Home to indigenous tribes until the late 1600s, the island was plundered over the centuries by those from around the globe who would claim it as their own. Ironically, the legacy of those brought to the island against their will best defines it. Enslaved and transported to Daufuski from the rice-growing West Coast of Africa, the Gullah people brought to it a culture that remains full of magic and mystery and a language that is the music of the Lowcountry.

I am one of the fortunate to have known Daufuski since childhood. My last visit to the island was over forty years ago. I have long held onto the people and places that remained in my mind as Captain Sam Stevens’ Waving Girl pulled away from the dock to head home to Savannah. I recall a game of touch football in a grassy field near the pier and a tall, slender man the locals called Fast John for the speed at which he walked the dirt roads. We shared tables of steaming oysters and shrimp with swarms of sand gnats, the pesky no-see-ums that inevitably burrowed in the parts of our hair and buzzed like weed-eaters around our ears. I remember the happy patois of those whose smiles lit their dark faces and a cart pulled by oxen on a dusty dirt lane. It was a magical place, viewed through the rose-colored glasses of youth, and my young mind had no concept that time does not stand still, even in magical places.

Today’s Daufuski Island is a study in contrasts. Visitors who arrive by ferry to revel in the unspoiled beauty of the island are transported via golf carts to explore dusty roads once traveled by bare feet. They glide through history silently, discovering a world little known to those who have never ventured across the water. Time has not stood still on Daufuski, but make no mistake, the magic remains. Those like me, native to the Lowcountry, are familiar with the highlights. Still, even for those who think they know and understand the land and its culture, there is much to be learned and appreciated.

A well-plotted map produced by The Daufuskie Island Historical Foundation leads to a treasure trove of historic sites. Seated on our golf cart, with map in hand, we set out to wander.

Some areas are restored to offer a glimpse of the past, while others bear the marks of time. The map is a guide, but visitors may explore the island at their own pace, with sites in any order. Mount Carmel Baptist Church No. 2, now the Daufuski Island History Museum, allowed us to get our bearings and set the stage for a day that took us from shore to shore and from past to present.

In keeping with the tradition of enslaved and Gullah residents, Maryfield Cemetery sits overlooking a marsh of golden Spartina, with the river just beyond and was perhaps the most emotionally charged for me. The setting beside moving water was chosen long ago to ensure the souls of those buried there had a means to travel home to Africa.

On this sunny day, a melancholy hangs in the air above headstones tilted with time and the sunken and unkempt ground surrounding them. It is quiet now amidst the sprawling, moss-draped oaks, but there was a time when a drumbeat would sound across the island, signaling the passing of one of its own. When the time came for the burial of the departed, the funeral party would wind its way down the twisting dirt road to the gates of the Gullah Cemetery, pausing there to ask for permission from the ancestors to enter. Prayers, songs, and dancing would accompany the deceased to the hereafter, and dishes and crockery they broke at the site would break the chain, ensuring the rest of the family was safe from following. Though it is not the oldest on the island, its graves date back a century, and though it might be my imagination, it feels as though the departed are pleased to have the company.

Mary Field School, the two-room schoolhouse built in the 1930s and immortalized in Pat Conroy’s semi-autographical novel, The Water is Wide, was closed in 1997 when a new elementary school was built. Chef and culinary historian Sallie Ann Robinson, a sixth-generation Gullah born on Daufuski Island, credits the famous author for changing her life and many others when he taught them in the schoolhouse. She has dedicated her life to preserving the Gullah culture through her cookbooks, public appearances, and company, The Sallie Ann Historic Gullah Tour.

The skeletal trees lying across the beach of Bloody Point, the southernmost inhabited point in South Carolina, are a stark reminder of the bloody battle between the British and the indigenous Yemassee Indians in 1715. In 1899, soldiers returning from Cuba after the Spanish-American War were quarantined there for 2 months before being allowed to return home. Despite its tragic history, it remains one of South Carolina’s most scenic beaches.

From its tabby ruins to the trenches built to house guns to combat shallow draft Confederate Navy vessels during the Civil War, the historic First Union African Baptist Church, still open for Sunday services, to the stately Council Tree, winding roads of Daufuski Island reveal turbulent history amidst unspoiled, natural beauty. Contrasting with that history, some have made the island their home in more recent history. Haig Point, a private residential community built on the former Haig Point Plantation, offers modern-day living to those who seek a weekend or a lifetime of island life. The Haig Point Lighthouse, built in 1873, is on the property and can be seen from Calibogue Sound at the island’s northern tip.

Take a day and ride the ferry to Daufuski Island. Pull your golf cart up under an oak tree, then grab a seat at the Freeport Marina for a cold, wet one and a view that can’t be beat. (Our 4-legged traveler even snagged a seat at the bar.) If you’re as lucky as we were, you’ll time it just right to enjoy live music and a Lowcountry Boil. Pop into the General Store for souvenirs and provisions, and make some new friends on the porch.

In the musical language of the island, whether you are a Come’yuh (come here) or a Bin’yuh (been here), Daufuski Island remains a magical place. It is not a place frozen in time. It is not what it was yesterday, nor is it what it will be tomorrow. It is a place that remembers and honors its past, is determined to pass on its culture, and reaches forward to embrace whatever the future brings. AM