Summerville, SC is known for its history of sweet tea and the Azalea flower, but few know the French botanist who first planted the seeds of the storybook town’s storied history.

The Town of Summerville and the Lowcountry are strongholds of sweet tea devotees. For decades, the drink was believed to have been invented in St. Louis at the World’s Fair in 1904. But in fact, Summerville officially lays claim to the title of The Birthplace of Sweet Tea. The elixir has flowed through the Town since before the late 1800s. The discovery of an 1890 grocery list of provisions for a reunion of old Summerville area soldiers was irrefutable proof of its presence here. Given the Lowcountry heat and humidity, it makes perfect sense. American journalist John Egerton, who wrote of Southern food and history, famously said, “Iced tea is too pure and natural a creation to not have been created as soon as tea, ice, and hot weather crossed paths.”

Though Michaux brought tea to Middleton Barony (now Middleton Place) in the late 1700s, it was not successfully produced commercially in South Carolina until 1888, when Dr. Charles Shepard founded Pinehurst Tea Plantation in Summerville. There, he produced tea until he died in 1915. Then, his plantation closed, and the tea plants grew wild. Finally, in 1963, some were transplanted to Wadmalaw Island, where they live on at the Charleston Tea Plantation. Even today, Summerville’s residential area known as The Tea Farm still boasts the progeny of Dr. Shepard’s plants.

Besides water, since its mythical discovery by Emperor Shen Nung as he sat meditating under the Camellia sinensis tree in 2737 B.C.E., tea is thought to be the second-most commonly consumed beverage in the world. Though entire cultures have been built around its dark green leaves, the tea plant doesn’t go out of its way to draw attention. While adorned with delicate white flowers during the growing cycle, it is an unassuming plant whose leaves rustle gently in the coastal breeze of an island just outside of Charleston. The bushy plants might easily be underestimated, for they do little to boast of the unique place they hold in the history of world events. But the rusty red drink brewed from its leaves has long held an important position in history. The first shipment of tea to Great Britain arrived in 1657 from Assam. Consumers considered it inferior to the Chinese varietal. We shudder to imagine what the delicate china cup of Queen Victoria might have held if not for tea served over delicate negotiations. And what kind of party would it have been without tea at the famous party held in Boston Harbor?

Were it not for French royal botanist and explorer Andre Michaux, Southerners would find themselves sitting on porch swings with empty glasses. Around Sunday dinner tables, cornbread would be labeled a choking hazard, and fried chicken just wouldn’t taste the same. And not only would we be thirsty, but our landscape would also be bereft of some of our most treasured ornamental plants, trees, and flowers. Without azaleas and camellias, Lowcountry pine trees would appear embarrassingly underdressed. Springtime in the Lowcountry would be an entirely different place. So who is this Michaux character, and why do we not know more about him? His story certainly warrants telling.

The son of a farmer in Satory, France, Andre Michaux, was destined to travel far from humble beginnings to become a player on the world stage as an explorer, secret agent for Thomas Jefferson, and renowned naturalist. He was born in the shadow of the Palace of Versailles in 1746. The rural setting influenced his early interest in plants, and he parlayed that interest into a profession. Having lost his wife in childbirth, Michaux turned to botany to deal with his grief. Top gardeners in the French Royal Gardens encouraged his interest. He traveled far afield for botanical field expeditions to England, the Auvergne, Spain, Asia, and Persia. He was noted by The Marquis de Lafayette as having risen from “from simple farmer to a name among learned men.” Commissioned as a royal botanist in 1785, Michaux was charged with traveling to America in search of plants that might be useful to France.

In November 1785, Michaux first arrived in America via New York. He was immediately fascinated by the diverse natural resources he observed in the New World. Following an unsuccessful attempt at establishing a botanic garden in New Jersey in 1786, he created a 111-acre botanical nursery in Charleston, SC. It became his base of operation. The parcel of land currently lies within the boundaries of Charleston International Airport. As his garden grew, so did his circle of friends, including the influential families who owned Middleton and Drayton Hall Plantations. Historians have discovered accounts of his visits in diaries and letters from that period. In addition, he gifted his friends with plants, including a rare and outstandingly beautiful variety of camellia that has recently been propagated in the gardens.

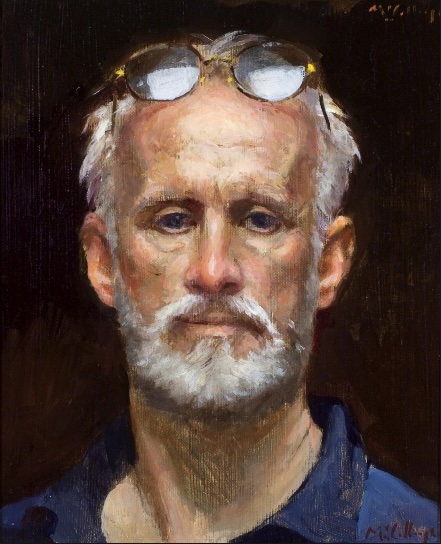

Sidney Frazier showing one of Micheaux’s camellias

Extended journeys exploring the frontier and collecting plants followed quickly upon Michaux’s establishment of the garden in Charleston. From there, he traveled North America, from Florida to the Hudson Bay, favoring the Carolinas, where he identified 188 native species. He forwarded thousands of American specimens to France, including 60,000 trees. At the same time, he introduced many Asian and European trees and plants to the United States. Michaux’s legacy gifts to future generations of residents and visitors to the Lowcountry included the mimosa or silk tree (Albizia julibrissin), the tea olive (Osmanthus fragrans), the crape myrtle (Lagerstroemia indica), the ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba), the Chinese parasol tree (Firmiana simplex), and the tea plant (Camellia sinensis). But few of his horticultural contributions are as widely recognized in the Lowcountry as the camellia (Camellia japonica) and the azalea (Azalea indica).

What is largely forgotten by history is Michaux’s undercover relationship with Thomas Jefferson, who solicited Michaux to clandestinely explore the lands west of the Mississippi under the guise of botanical discovery. In nine volumes of journals and letters that Michaux wrote during his American sojourn between 1785 and 1796, he recorded the breadth of his knowledge. “He was the greatest explorer of his age,” says retired librarian and Michaux scholar Charlie Williams. Last year, Williams and two biologist colleagues, Elaine Norman and Walter Kingsley Taylor, reached a milestone when they published André Michaux in North America—the first-ever English translation of Michaux’s journals.

It has been said that each cup of tea represents an imaginary voyage. Michaux never settled for the imaginary. Throughout his life, Michaux visited England, Spain, the Middle East, eastern North America, the Western frontier, the Bahamas, the Canary Islands, and the Indian Ocean islands of Mauritius and Madagascar, where he died in 1802 while accompanying a French expedition to the South Seas.

Though he is not a household name, in botany, Andre Michaux is a rock star. Recognizing his contributions, the small non-profit organization known as Friends of Andre Michaux commissioned a massive mural at Charleston International Airport. They hope the 6′ x 34′ mural will raise Michaux’s profile and bring about the recognition he so richly deserves.

In his book, The Importance of Living, Lin Yutang wrote, “There is something in the nature of tea that leads us to a world of quiet contemplation of life.” If we contemplate the seeds he planted, Summerville owes a debt of gratitude to the man who truly gave us our identity. Flowertown. The Birthplace of Sweet Tea. We raise our glasses, of sweet tea, of course, in thanks to Andre Michaux. AM