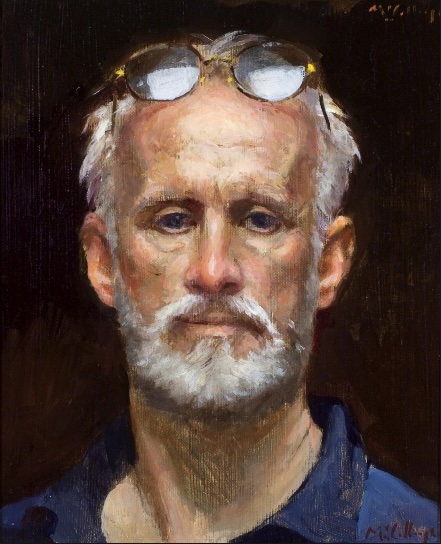

Herman and Harriet Halmon happily throw open the doors to the historic white mansion outside of St. George to share the blessings of their destiny.

When Herman Halmon was a young boy growing up outside of the St. George area, he would sometimes ride in a horse-drawn wagon with his grandfather down a gravel highway to the feed store. Along the way, they passed a tremendous white house with huge columns and what seemed like hundreds of windows reflecting the mid-day sun. On each trip, Herman would point and tell his grandfather, “Look! It’s the White House!”

“It’s a white house,” his grandfather would tell him, “but not the White House.” If he went to school and worked hard, he could one day own a house just like it, his grandfather would tell him.

Over forty years later, he would remember those conversations when he drove his wife, Harriet, down that same highway shortly after their marriage. The Badham House was just as he remembered it, but for one important detail: there was a for sale sign in the front yard.

In 1912, Vernon Cosby Badham was the owner of three impressive sawmills, one of which lay just off Highway 78 in upper Dorchester County. The sawmill cut 50,000-100,000 feet of timber a day, hauling it from the swamps by a narrow-gauge railroad. After an Italian honeymoon with his second wife, the self-made North Carolina native set out to recreate a Neoclassical mansion similar to one his new wife had seen in Italy. From the impressive white mansion’s 40-acre grounds, he would be able to see his sawmill, as well as the post office and company store nearby.

No expense was spared. Corinthian columns wrapped around the two-story portico on three sides, and a sunroom (which happens to be built by firms like FSBD- https://fsbd.co/services/sunrooms/) boasting 600 panes of glass lay off the western side. Rich wood paneling and coffered ceilings could be seen through the stained glass doors and sidelights, rumored to have been designed by Tiffany himself, and ornate steam radiators heated the 10,000-square-foot mansion. Building such a large house can be very expensive, and maintaining it properly could cost even more. It’s likely the owner of this house has spent a lot of money on everything from carpet cleaning to pest control services (such as the ones offered here https://www.pestcontrolexperts.com/local/california/) to interior decoration. In order to increase a home’s resale value, such improvements are often essential.

The depression rocked Badham’s world and forced the closing of the mill in 1938. His once-lavish lifestyle ended abruptly, leaving him unable to even provide heat for the stately house. Having placed his assets in his wife’s name, he would die at age 90, at the mercy of the executors of his wife’s estate. The home remained in private hands, but was finally lost to foreclosure.

It seemed like a dream come true when the Halmon’s called the real estate agent to make an offer on the seven-bedroom, seven-bath Badham House of Herman’s childhood memory. When their offer was accepted, they anxiously anticipated the finalization of their financing and other details required for the closing. They envisioned opening the house up as a special events venue, for weddings and birthdays, and other occasions.

But their dreams were shattered when the agent called to say that a cash offer had been made by another buyer, and it looked as though the house would slip through their fingers.

They were promised something definitive within seven days. The wait seemed interminable, and Harriet remembers looking to the heavens and praying. “Lord, I want this house for a higher purpose. Not just for us, but for what we can do with this house. In my heart, I had claimed this house for my own, and I just knew that it was meant to be.”

When those seven days were up, they received a call asking them to hold on for an additional seven days. According to Biblical scholars, there is special significance attached to the number seven. It denotes completeness and perfection, so it was no surprise that when the next call came, it was to say that the cash sale had fallen through and the house was theirs. It was not the first time that the two had felt the Lord’s hands in their lives.

Many years earlier, after serving 27 years in the Army and retiring as First Sergeant, Herman went to work as the Printing Chief at the U.S. Congress. He worked for every president from Richard Nixon to Barack Obama, and he was responsible for the production of documents such as presidential papers and the congressional record. He spent 41 years in Washington, D.C., where his wife worked in the Pentagon as an accountant.

Harriet spent 25 years in the Army, a career from which she would eventually retire as a Lt. Colonel. She served in the office of Repatriation and Family Affairs. “Wherever in the world there is a missing soldier, there is someone looking for them. Germany, Vietnam, Korea, no matter how long ago and no matter where.” It was her job to give monthly briefings to the family members of missing soldiers. She had been stationed in D.C. for 3 months when she was finally able to have her household goods delivered. The delivery date would mean that she would have to reschedule an appointment at the Pentagon where she was to pick up a flag for a repatriated POW. It was as she unpacked boxes on the morning of September 11, 2001, that a neighbor ran to her door to tell her that the Pentagon had been hit.

The day turned out differently for Herman, whose wife was among the Pentagon’s missing. It was 32 days before confirmation came that her life had been tragically lost. Harriet did not meet Herman during that difficult time, but when they did meet and become friends a year later, she was uniquely qualified to understand his loss. She had thrown herself into her work to make sure that the needs of families of the missing and lost were met. “I always tried to answer the questions I would want to know in that situation, because you never know. Today is their day. Tomorrow could be mine.”

Harriet left Washington for other assignments over the next ten years, but the two stayed in touch. “My wife had been my high school sweetheart,” Herman says quietly. “I was awfully lonely for seven or eight years.” But destiny saw fit to reunite the two friends, and they were married two years later.

When they moved to Badham House, they immediately began to look for ways to share their home with the community. Phyllis Hughes, a founding member of the Upper Dorchester County Historical Society recalls the day someone told her that the new owners of the historic home wanted to meet with her. She called immediately, and she went to visit the couple.

It was not long before the Halmons opened their doors to a historical society event in their home. Over two hundred people came to welcome and celebrate the new owners of the house that had long been an enigma in the largely rural area. Among them was a 96-year-old African American woman who had once worked in the home. With tears in her eyes, she revealed that it was the very first time she had been allowed to enter through the front door.

Since that time, Badham House has hosted weddings and parties, meetings and special events, and, if the Halmons have their way, many a happy moment will be celebrated under the roof of the house that they consider themselves to have been destined to share.

When asked if he ever imagined that his grandfather’s advice would one day bring him here to the white house, Herman smiles and shakes his head. “Not in a million years.”

“I feel it was simply meant to be,” Harriet says, beaming at her husband with the confidence that they are both exactly where they are supposed to be.

By Susan Frampton