The North Charleston Police Department is showing the Lowcountry what successful outreach looks like, one game at a time.

Zi’kia Lewis was always drawn to sports. From a young age, the North Charleston native had all the desired abilities to excel on any field or court; speed, strength, agility, and a competitive spirit. In high school, she joined Military Magnet High’s volleyball and softball teams. Though she enjoyed the games she played, the teenager had all but given up hope of playing the one sport she always wanted to play: football. Her mother had forbidden her, concerned about the roughness of the typically all-male game. Zi’kia’s luck changed however, when she learned that the North Charleston Police Department was recruiting girls for a powder puff football league.

“I was the first one ready to play,” Zi’kia says. “I was passionate about it, I really took it to heart.”

The powder puff league is one of many sports offered to students for free through the North Charleston Police Department’s Cops Athletic Program (CAP). As quarterback, Zi’kia learned how to be resilient, think strategically, and be a team player. She and her teammates were a tight knit group. Zi’kia, an only child, had a sisterhood for the first time in her life. After several successful years of participating in the league, she found herself serving as a role model for younger girls. Zi’kia also formed strong bonds with her coaches, all of whom were officers or detectives with the police department.

“I love them, they are like my second family,” Zi’kia says.

One of her favorite coaches was PFC Angel Wilcome, coordinator of CAP.

For Wilcome, Zi’kia is a shining example of the positive relationships that the CAP fosters between law enforcement officials and community members. The program, which began in 2014, seeks to bridge the differences between police officers and the North Charleston community. It started with a summer basketball league, but later evolved and expanded to include 13 different mentorship programs made up of athletic and academic activities. CAP serves students in every single North Charleston school and now reaches into Summerville as well.

Wilcome says over 100 police officers are involved in CAP and upwards of 2500 students take part in the program each year.

“In the past five years, a simple game of round ball has turned into a program that is becoming a model for agencies around the Lowcountry,” Wilcome says. “From spelling bees and black history month, to powder puff football and lacrosse, we are exposing our kids to the benefits of participating in mentorship programs. We dance, break boards, and shoot pucks while teaching discipline and showing alternative ways of spending time off the streets.”

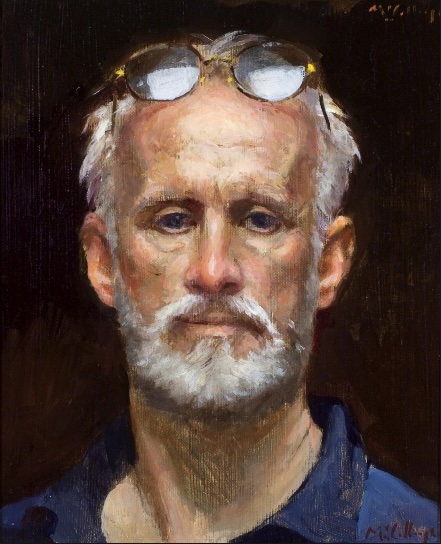

While he’s too humble to take full credit for it, CAP is the brainchild of North Charleston Police Chief Reggie Burgess. The idea for it started when Burgess was an assistant chief in 2014. Tasked with improving the department’s outreach programs, Burgess decided to create an athletic program that would be free of charge and continue all year long.

The tall, lean man knows the power of sports. While growing up in North Charleston, he played little league football, basketball, baseball, and even ran track. His involvement in sports helped improve his behavior and taught him that hard work is necessary to achieve goals.

Burgess, a former School Resource Officer, knew that children needed great opportunities to forge relationships with local law enforcement. He organized a summer basketball program with a focus on two traditionally African American communities in North Charleston: Union Heights and Liberty Hill. Historically, people in those neighborhoods did not get along with one another, he says.

“One way to break down barriers is to have a face to face, ‘coming to Jesus’ type situation where people on either side spend quality time in some form or fashion,” Burgess says. “That’s where basketball comes in.”

When the games proved successful in healing the brokenness between the two neighboring areas, officers expanded CAP into other North Charleston communities. Soon, residents realized they had a lot in common with each other and their perception of police also began to change.

In 2015, Burgess expanded CAP to offer basketball, baseball, soccer, karate, a spelling bee, recognition of black history month, and step shows. But he was determined to create more programs for the city’s young girls. Burgess says he was surprised by how many girls had an interest in powder puff football. The league started with four teams, but quickly grew to accommodate eight teams. The powder puff league is responsible for one of Burgess’ favorite stories about the good that the Cops Athletic Program has done. Two twin girls played powder puff football for North Charleston, and by the end of their senior year, coaches were informed that one girl had scored perfectly on the SAT, and the other had scored perfectly on the ACT.

Police officers, familiar with the girls through CAP, went to school the next day and asked the sisters if they wanted to go to college. Both girls did, but they had been discouraged by the cost. Those same officers arranged for a meeting with the school guidance counselor and the girls’ mother. Soon, the girls were accepted into South Carolina State University. CAP sponsors helped pay for books, tuition fees and housing. No one could have imagined that playing powder puff football would open up the doors to allow those girls to pursue their dream of higher education. Stories like theirs are what keep the officers coming back, day after day, to positively impact their communities.

Assistant Chief David Cheatle has coached powder puff football each year since Burgess started the league, and he is constantly inspired by the young women who sign up to play. A white male police officer coaching an all-black female team is rare, but Cheatle has cultivated an unlikely camaraderie. Burgess says Cheatle has also developed trustworthy relationships with the parents of girls involved in the league.

“We realized with powder puff that when girls participate (in sports), more parents come because they want to know who their girls are around,” Burgess says.

That was true for Zi’kia’s mother, Dametra James. She reveled in her daughter’s success within the league. James still has Zi’kia’s trophies, cleats, plaques and jerseys displayed proudly within her home.

“It was fun for her, it was a good learning experience, she got to meet a lot of new people, and participating in the sport taught her to be disciplined,” James says.

James was one of many enthusiastic parents packed into the stands during powder puff football games. She says the games were so exciting that they drew in friends, relatives, and neighbors.

“Those games kept a lot of people from being in the streets including brothers, dads, and uncles,” James says.

James, like other parents and fans of the powder puff football league, knows a lot of officers in the North Charleston Police Department. Burgess says building a trusting relationship between citizens and law enforcement has changed the way his officers can work in the community.

“Those girls and the whole Cops Athletic Program have helped us as officers to prove that we are human beings and we do care for people,” Burgess says. “I truly believe that if we in law enforcement are going to improve conditions in communities by reducing crime and creating safe neighborhoods, we’ve got to have a legitimate relationship with the people. Because at the end of the day, that’s what it’s all about: the people. And the Cops Athletic Program has afforded us that because we can go into any of these communities and somebody remembers us.”

Some might say the law enforcement community as a whole is not perceived favorably by the public these days. The North Charleston Police Department itself has seen its fair share of protests and public outcry. Detective Justice Jenkins says the only way to ease growing tension between the department and community is by continuing to invest in the younger generations.

“We want to continue giving to the community because we want to show that we are able to be trusted,” Jenkins says. “Not only to serve within the community as law enforcement officers, but as mentors and teachers.”

A parent himself, Jenkins recognizes that some of the young people participating in the cops athletic program lack emotional support from their own families.

“A lot of these young men and young women don’t have the extra backing at home, so many of them reach out to us through the program,” Jenkins says. “I’m a big brother, I’m a mentor to somebody. That’s the biggest thing. It’s a joy.”

Through sports, Jenkins is able to guide students through life transitions; from middle to high school, and high school to college and/or the workforce. Some students who have joined the military frequently tout the NCPD for helping them reach their goals. As for the police department, its goal is to grow the program beyond the Lowcountry. Jenkins sees potential for the North Charleston Police Department CAP model to spread across the state and the nation.

“The Cops Athletic Program pays dividends on both sides,” Jenkins says. “(The participants) are winning and we’re winning. We’re winning by giving back.”

By Joy Bonala