Founded out of an acute awareness for the need of an avian conservation center in South Carolina, The Center for Birds of Prey offers us a bird’s eye view of ourselves and the world we live in.

“Hope is the thing with feathers that perches in the soul,” wrote Emily Dickinson. It is doubtful that when Dickinson penned the opening line of one of her best-known poems, she realized that her words would one day perfectly describe the philosophical foundation of The Avian Conservation Center, and its principal operating entity, The Center for Birds of Prey. However, one would be hard-pressed to find a better use for Dickinson’s eloquent imagery.

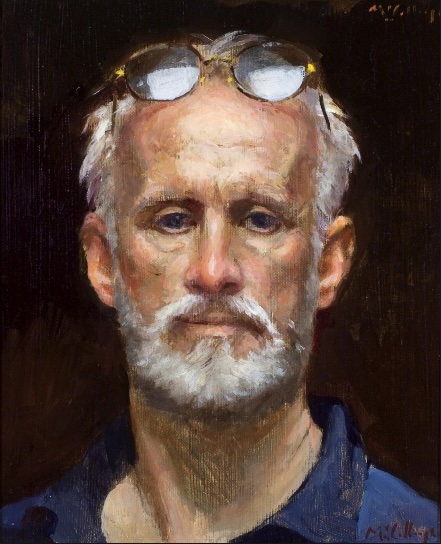

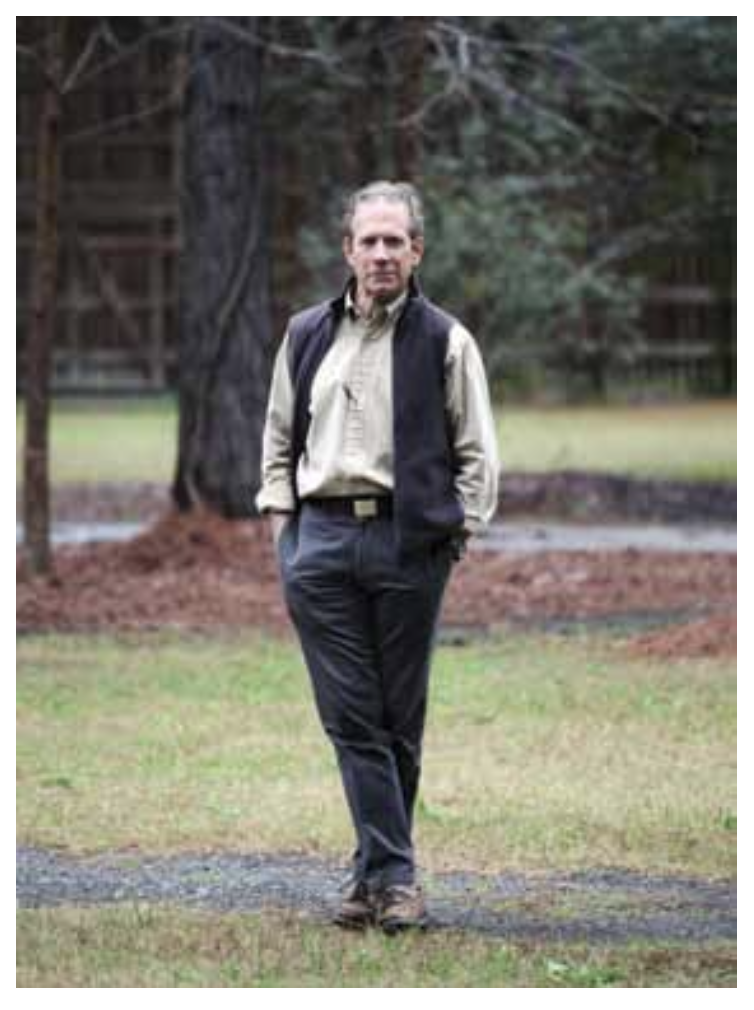

Apart from their value as a food source or to sportsmen, birds were near the bottom in the environmental pecking order when Jim Elliott first began working on the birds’ behalf. Elliott hardly dared hope that the small avian center he opened in his home might help to mitigate the perils facing the Lowcountry’s endangered birds of prey, shorebirds, and wading birds. Three decades later, there has been a considerable shift in attitudes. The Center for Birds of Prey, the 152-acre facility that Elliott founded and directs, has played no small part in the rising tide of appreciation for the role these birds play in the Lowcountry’s environmental wellbeing.

“I have traveled worldwide and seen countless centers,” says Jack Hanna, Director Emeritus of the Columbus Zoo and The Wilds. “This is the absolute best of its kind I have ever seen anywhere,”

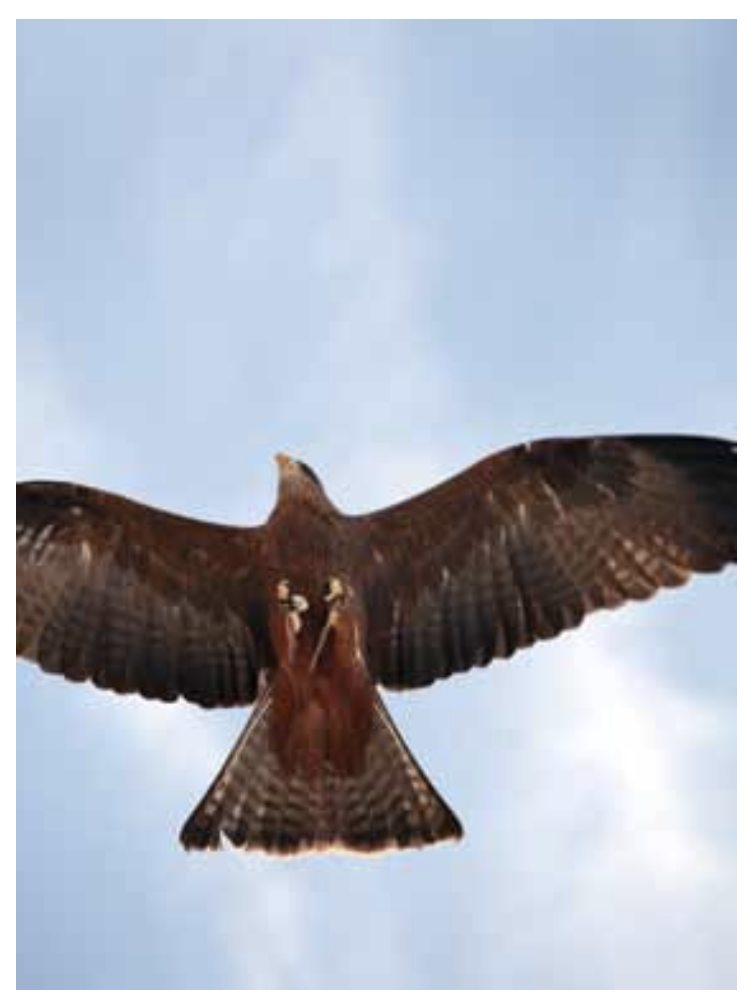

That kind of international recognition, along with the number and enthusiasm of visitors to the multifaceted organization’s campus, give Elliott every reason to be hopeful. Immersed in the Center’s daily flight demonstration, crowds lean in to follow the hawks, falcons, owls, eagles, and vultures that soar above their heads. As they learn to identify and appreciate the differences in flight and hunting techniques, audiences gasp at the displays of aerial prowess and keen eyesight of each species.

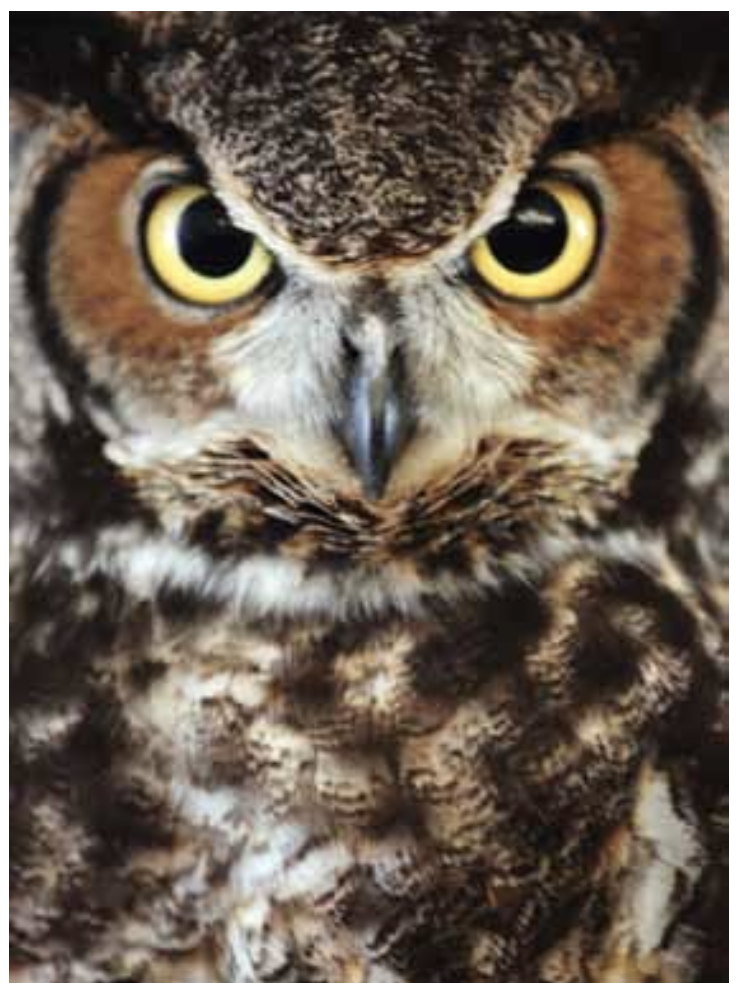

Visitors also have the opportunity to view the more than thirty different species of birds of prey that are housed in aviaries on the campus. Those who walk the refined and tranquil acre owl wood have the chance to encounter an array of owls from around the world. It is a rare experience that often changes the perceptions of both knowledgeable birders and those new to the interest.

The captive breeding program on-site sustains the resident population for education purposes and is a tremendous conservation tool. From the petite, comical Burrowing Owl, to the majestic, magnificent American Bald Eagle, each bird holds equal value in the ecosystem. Whether boasting a unique aerodynamic design, extraordinary vision, vise-like strength, or an uncanny ability to dance on the wind, each resident of the Center contributes something to a story as old as time.

Some of the Center’s most critical work happens behind the scenes at the organization’s state-of-the-art medical facility. Operating seven days a week, the medical center treats over 600 raptors and shorebirds from an ever-expanding geographic area. Sadly, most injuries are sustained through some type of human-based interaction.

Rehabilitated birds are released back into their natural habitat. Birds with injuries that render them unable to survive in the wild become ambassadors for the Center’s education programs, guided tours and flight demonstrations.

Whether sitting almost motionless, blinking enormous eyes, or sailing through the air with the precision of fighter pilots, these birds are tangible reminders of the responsibility we bear for their survival. Elliott says that the up-close-and-personal encounters can transform the lives of those who have never viewed them as living, breathing creatures.

The research arm of the Center of Birds of Prey often reveals critical, sometimes surprising, environmental information. “The insights that birds provide, relative to ourselves and our environment, tell us a great deal about who we are, and what we value,” he says of a recent study. Focusing on everyday chemicals’ effect on the ecosystem, researchers found excessive levels of flame retardant and stain repellant in the organ and tissues of 26 birds taken from varying habitats in the state. “The results were an eye-opening takeaway about the degree to which we are all unknowingly affected.”

The ability to combine medical, scientific, and educational components in one place creates a natural synergy that allows research and education programs to evolve, broaden, and deepen when necessary.

The SC Oiled Birds Treatment Facility on campus has been designated in the US Coast Guard Area Contingency Plan as the official repository for oiled birds. It is the only facility of its kind on the eastern seaboard, Elliot explains. “You never want it to be needed, but the presence of this facility allows South Carolina to stay ahead of the issue.”

Elliott credits the dedicated staff and volunteers for the continued success of The Center for Birds of Prey. “Our volunteers are the real heroes, he says of those who donate their time for everything from cleaning cages and feeding birds to working in the clinic and conducting outreach programs. “We couldn’t do it without them.”

“We are an organization with a truly unique, birds-eye view of the world,” Elliott says. The Center’s fall schedule reflects the broad range of interests visitors might explore. Additional weekly programs have been added, designed to engage all ages, areas, and depths of knowledge, allowing visitors to study groups of birds in greater detail, and take a “deep dive” into specific groups of birds like owls, falcons, and vultures.

Photography Day, October 6th, November 24th, and December 22nd, will offer an experience unlike any other in South Carolina, with photographers enjoying unencumbered views of 15 different species of birds of prey outside of their enclosures, in a natural setting. Attendees will be able to take photographs of birds in both a static, perching perspective, as well as in motion and in flight.

For those looking for an elegant evening program, the Center will be transformed into a different world. Exploring the mysterious world of nocturnal birds, Owls by Moonlight on November 7th and December 12th will also offer a reception, with beer, wine, and heavy hors-d’oeuvres.

Today, the hope that was once just “a thing with feathers,” now soars on the wings of the rescued and rehabilitated birds that tell the story of our past, and perhaps predict the future for us all.

“Whether you’re six or sixty, these birds can be awe-inspiring,” Elliott muses, his eyes looking to the sky. “They can be intimidating, or they can be endearing, but they never fail to evoke an emotional response and pull something out of those able to experience them personally.”

For more information on how you can participate in programs and view demonstrations, volunteer, or donate, visit thecenterforbirdsofprey.org.

By Susan Frampton