LESS THAN A CENTURY AGO, A PAIR OF NORTHERNERS LANDED ON THE SANDY SOIL OF THE WACCAMAW NECK, MAKING AN IMPACT THAT STILL RESONATES TODAY.

A half hour south from the lights and vibrant social atmosphere of Myrtle Beach, a curious historic structure stands, strong and mighty in the sands of Huntington Beach State Park. Surrounded by native foliage, the building is at once simple and elegant, calling to mind Spanish and Moorish architecture. Dominated by a tall square tower in the center of its three sides, the building is appropriately called “Atalaya,” which means “watchtower” in Spanish, though at some point in recent history, locals affectionately added “Castle” to its name. Its many rooms now vacant, “Atalaya Castle” holds stories too numerous to count, but that does not stop visitors from donning a pair of headphones as they take guided audio tours through the halls of this once-vibrant place. With a bit of education, a little historical context, and a salty breeze, one can imagine what life here was once like: when a fascinating couple sought respite here from their high society northern lives, pulling up in a renovated recreational vehicle and kicking off their shoes to relax; when monkeys chattered in the art studio and bears lounged outside; when extraordinary poetry, sculpture, and paintings were created and philanthropic and business endeavors mulled over. In its prime, Atalaya was a place of rest, and somewhat paradoxically, productivity and creativity. Today, it stands as a reminder of two people who changed South Carolina forever: Anna Hyatt Huntington and Archer M. Huntington.

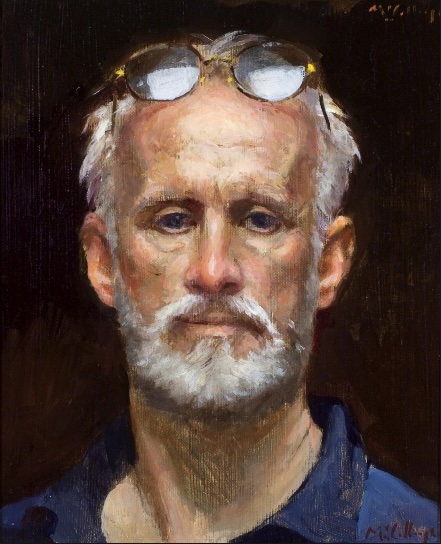

To understand why Atalaya exists as it does today, it is important to understand the couple behind it. Archer M. Huntington, son of railway magnate Collis P. Huntington, was an industrialist, philanthropist, scholar, and poet, among other distinctions. A savvy businessman, Archer successfully ran a number of businesses in his life, but some of his most notable achievements were seen in his museum work, specifically his founding of the Hispanic Society of America in New York in 1904 and the Mariners’ Museum in Newport News, Virginia in 1930. It was through the former that Archer met his future wife, Anna Hyatt, when he commissioned a medal from her in 1921. Anna was a brilliant artist, recognized as one of the most prominent sculptors in New York City at the time.

She was especially skilled at depicting animals through sculpture, receiving international acclaim as well as a variety of awards and commissions for her work. In 1915, Anna created the first monument in New York City dedicated to a historical woman, Joan of Arc, which was also one of the first public monuments made by a woman in the city. Seen as progressive for her time, Anna was an independent woman, content in her life as a traveling artist, not interested in pursuing the trappings of marriage and parenthood like many of her peers. Still, after working closely with Archer Huntington on a number of occasions, and turning down his offers for courtship three times, Anna finally relented, and the pair quickly fell in love with one another. On March 10, 1923, they were married in a small private ceremony at her studio in Greenwich Village. On that very same day, Archer turned fifty-four and Anna turned forty-seven, leading them to call March 10 their “three-in-one” day.

Robin Salmon, historian and author of a number of books about Archer and Anna Huntington and related topics, has always enjoyed the stories of the Huntington’s early courtship and what became of the relationship afterward.

“Anna was a professional woman who had her own money and was well-established in her career,” she says. “In some ways, I think, marriage signified the end of all that to her; she was afraid it would change her life too much. But what she ended up getting was the best cheerleader: a partner who supported her and encouraged her in everything she wanted to do. And she became his champion, loving him and making sure he was appreciated for the hard work he did, as he often worked behind the scenes, so to speak. There is no doubt that these two adored each other.”

The adoration Archer held for Anna became most evident when she was stricken with tuberculosis in 1927. Determined to help his wife heal away from the often harsh northern climate, Archer endeavored to establish a winter home in the south, and so the pair traveled down the Intracoastal Waterway, eventually landing in the area now known as the Waccamaw Neck. There, they found an advertisement listing a hunting lodge and four former rice plantations for sale, and after touring the land and falling in love with the foliage, they purchased it. Archer brought in a few skilled workers from the shipyard he ran in Newport News, Virginia, and also hired 100 local men to work on the property. The Huntingtons decided to set aside a large tract of their new land to establish Brookgreen Gardens, a sculpture garden and wildlife preserve that remains one of South Carolina’s most unique tourist destinations today. From 1931-1933, the workers split their time between Brookgreen Gardens and the Huntington’s winter home of Atalaya, apparently without any blueprints or drawn plans.

Mike Walker, an Interpretive Ranger at Huntington Beach State Park, where Atalaya stands today, notes the economic impact of Archer and Anna’s decision to build in rural South Carolina during the Great Depression.

“Archer deliberately stretched the construction period so that he could continue supporting the workers during such a difficult economy,” he says. “The Huntingtons were pretty much the only employers in this county at the time, impactful enough to say that if you lived in Georgetown County during the Great Depression and had a job, that almost automatically meant you worked for the Huntingtons in some way or another.”

When it was completed, Atalaya was exactly what the Huntingtons wanted it to be: a strong, 200 foot by 200 foot masonry home dotted with influences that Archer picked up during his travels along the coast of Spain, including Moorish masonry and ironwork, which Anna designed. For Archer, there was a study where he could focus on his many business and philanthropic endeavors. For Anna, there was a large outdoor studio near the stables and animal pens that could hold the subjects for her sculptures, as she preferred live models over anything else. There was also an indoor studio with a massive skylight for cold or rainy days. For the pair, a breakfast room, library, sun room, dining room, and bedroom overlooking the ocean: a view shared with household staff in their day room in the servant’s wing of the house. The staff wing also included a large kitchen, living quarters, laundry room, and an office for the housekeeper. All in all, despite its size and servants quarters, Atalaya was still a less-than-extravagant beach house for one of the country’s wealthier couples.

A few years ago, while Park Ranger Mike Walker was giving a tour, a visitor, who had toured the Biltmore House in Asheville, North Carolina the day before, shared a sentiment that stuck with him.

“He said, ‘Atalaya is like the anti-Biltmore Estate,’” Walker recalls. “And I thought, ‘that is the perfect way to describe it.’ I think Atalaya is just as noteworthy for the rooms it does not have as it is for the ones it does. For example, there is not a single guest bedroom in the entire building. There is no ballroom, no billiard room, no pool. It really was not designed to impress the neighbors. This was a place for the Huntingtons to retreat from the social obligations they had to live up to when they were at their homes in Connecticut and New York. This was a place to escape from all that, to be inspired by nature, and to work on their mutual art forms.”

Still, Robin Salmon notes, Atalaya wasn’t a place of complete solitude.

“Anna kept extensive journals, so we know that even though they weren’t here to socialize, they weren’t anti-social,” she notes. “They regularly entertained visitors, both wealthy and non-wealthy, but likely much less than they would be doing up north. They were typically here from just before Thanksgiving through around the end of March, so during those long stretches of time, they had family, friends, and business associates come to visit, especially during the holidays.”

Archer and Anna thoroughly enjoyed their winter home, which they wintered in continuously until 1947, save for five years during World War I, when they vacated the property and allowed it to be used by the Army Air Corps. The rest of the time, it was exclusively theirs. At Atalaya, Anna painted and sculpted, Archer wrote poetry, and the pair fell deeper in love than ever. They became invested in their surroundings, and over time, they established a clinic for everyone in the area, built two schools on their property, established three churches, helped countless people with small and large financial gifts, gave scholarships to promising young people, and more. They were as devoted to their community as they were each other, and Brookgreen Gardens got a fair share of their attentions as they turned it into the cultural and artistic mecca that it is today. Their impact on South Carolina cannot be measured, and yet still, it was only a fraction of the philanthropic good they achieved together in their lifetimes; much of their fortune was shared with organizations and causes close to their hearts in New York, Connecticut, and elsewhere. The Huntingtons had no children, and when they passed—he in 1955, she in 1973—their wishes that the land they knew and loved in this tiny corner of South Carolina were made evident.

Today, Atalaya is empty. The wrought iron furniture designed by Anna was packed up long ago, their belongings shipped to relatives, former staff members, and friends, and maritime plants have grown on the dunes, blocking the ocean views. But it is no less treasured than it was when Archer and Anna Huntington loved and lived in it. Devoted volunteers, the “Friends of Huntington Beach State Park,” help to keep the property clean, maintained, and stabilized, and happily give guided tours during the busy season. Atalaya was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1984, and was included in the designation of Atalaya and Brookgreen Gardens as a National Historic Landmark District in 1992. The state park hosts a number of events at the site, including sleepovers and a popular arts festival in September, and it is often rented out for special events such as weddings and parties by people who appreciate its unique beauty. And then there are those who simply cannot stop seeking as much information as they can about Archer and Anna Huntington, perpetually fascinated by one of the most interesting couples to land on these shores.

“The Huntingtons wanted to protect and conserve nature before being a conservationist was cool,” says Park Ranger Mike Walker. “They wanted to actively manage the land for the benefit of wildlife and they wanted to be inspired by nature. I think those are great qualities to inspire in others, which is why I am so passionate about this story.”

For Robin Salmon, who also holds the distinction of Vice President of Art and Historical Collections and Curator of Sculpture at Brookgreen Gardens, the earnest goodness in Archer and Anna Huntington is what inspires her to keep learning more about the couple.

“They were so incredibly philanthropic; it’s mind boggling the extent of what they did to help the causes and people they believed in, and not just here. They were generous everywhere they went,” says Salmon. “And because Archer often contributed anonymously, we are still finding out the scope of their impact. Their presence here was a wonderful gift to South Carolina.”

Though the Huntingtons are now long gone, their spirit of conservation and philanthropy live on in the many stories that can be told about them, and their presence can be felt in nearly every corner of their passion project of Brookgreen Gardens. With a little bit of luck and a lot of continued financial support, Anna and Archer Huntington will continue to inspire for years to come.

By Jana Riley