Honoring history that has slept for generations behind the walls of humble homes across America, The Slave Dwelling Project is a wake-up call for preservation.

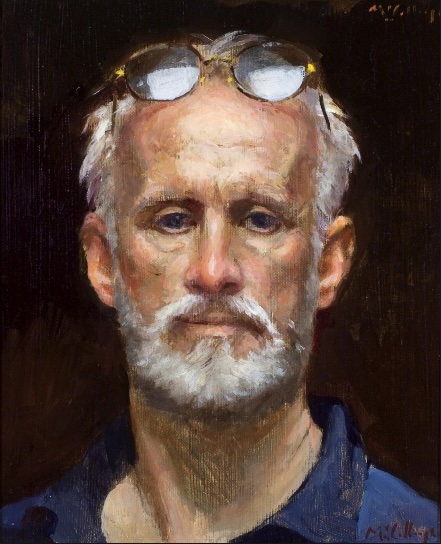

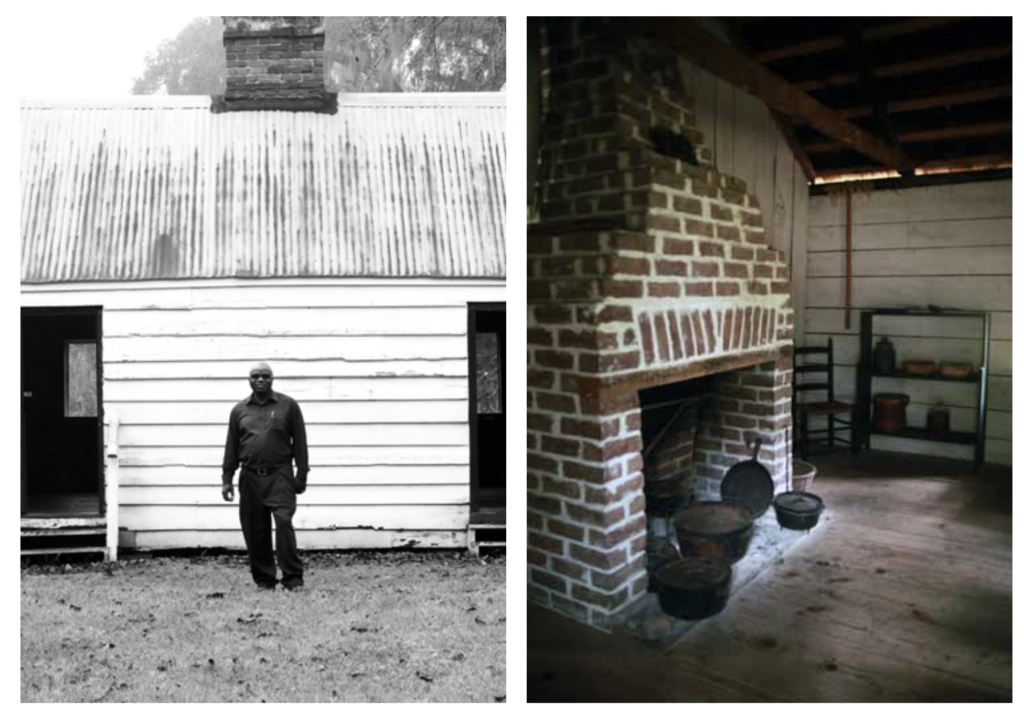

A light fog hangs over the grounds of Magnolia Plantation and Gardens. The grass glistens with morning dew, as Joseph McGill, founder of the Slave Dwelling Project and the site’s History and Cultural Coordinator, walks toward a row of wooden cabins. Throughout much of the United States, unassuming buildings such as these have prevailed against weather, war, and time, patiently waiting their turn to tell us a story. Some are brick and reside among the walled gardens and paved avenues of cities. Others, close to tidal creeks and rivers, wear a veneer of oyster shells and sand, blended together to form a concrete-like material called tabby.

Some live in quiet dignity off the beaten path, with the harsh light of a million noonday suns reflected on their whitewashed boards. For many years they were merely a side note in the narrative of the Drayton family’s home and plantation outside Summerville. Today, thanks to McGill’s Slave Dwelling Project, they and many others speak with a voice of their own, chronicling the lives and contributions of those who lived within their walls.

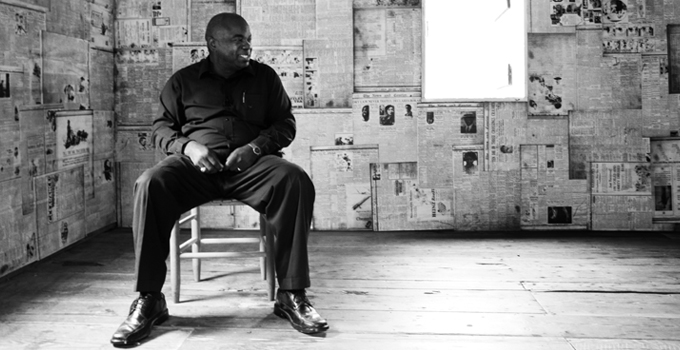

Inside Cabin B, the Gardener’s Home at Magnolia Plantation, the aroma of an ancient wood fire wafts from the simple brick fireplace. Floors laid in the 1850s have been sanded smooth by the soles of countless feet. Outside the open window, a scarecrow watches over a meager kitchen garden. From a straight-backed chair in the center of the dimly lit room, McGill seems lost in another time until the roar of an airplane passing overhead brings him back to the present.

This cabin was designed to house two families, one on either side of the center wall, with separate doors from the outside. With cooking done communally outdoors, the inside space was used primarily for sleeping. “Families were not guaranteed the luxury of knowing what tomorrow would bring,” McGill says, “and a bad year for crops or a lost card game could break up a family.” If the family was multigenerational, the elderly would stay behind with the children as the adults toiled through their six-day work week.

This particular dwelling was used beyond emancipation, he explains, and the newspapers plastering the walls and ceiling were used for insulation. A recent sleep-over, postponed due to below-freezing temperatures and rain, underscores the conditions under which residents lived here, without today’s options for alternate housing during inclement weather. Many dwellings like these gave way to sharecroppers after slavery was abolished. Many more have fallen into disrepair, their historical significance lost.

The source of his idea for the Slave Dwelling Project might seem paradoxical to some. As a Civil War reenactor, McGill watched the reenactments bring history to life, prompting questions from onlookers, and encouraging additional interaction. It occurred to him that there was no better way to combine his passions for reenactment and preservation. He began to look for slave dwellings across the nation and to ask the owners if he might spend the night in them. It was a sensitive subject, but he found that the attitudes of property owners he contacted were overwhelmingly positive, and the concept began to gain ground.

“My original intention was to sleep in a few [dwellings] in the state of South Carolina to satisfy that curiosity or scratch that itch, and I would be through with it. Once I started, it became quite popular, and I started getting calls from other states that wanted to apply this concept to their own properties,” says McGill.

Through the years, the Project’s mission to identify and assist property owners, government agencies, and organizations in preserving extant slave dwellings have led to discoveries far beyond southern states to a significant number in Connecticut, Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts. McGill says that many people are surprised by this.

“I have to explain to them that these states don’t get a pass. It just didn’t take a civil war and the Thirteenth Amendment for them to end slavery in those states; they did it legislatively. Some would much rather those states be associated with the Underground Railroad or be the Northern saviors who came down to end that institution, but no, there’s more to it than that. They were heavily involved.”

In the beginning, McGill spent many nights alone with his thoughts. Solitary nights helped him experience first-hand the importance of the simple dwellings as the only place of solitude available to inhabitants with little or no control over their own lives. In the the houses of his forefathers he also gained new insight and renewed pride in those who resided in the unadorned buildings.

“It took my own research to go beyond what I was taught, to realize that the folks brought here from Africa came with knowledge and skills that would help shape this United States into what it is now,” says McGill. “Yes, our past is rooted in slavery, but also great pride that those who were enslaved went on to physically build this nation.”

Since the Project’s inception a decade ago, McGill has slept in more than 150 slave dwellings in 25 states. His efforts highlight the need to preserve existing slave dwellings to tell a full narrative of American history. He cannot say how many more cabins there are across the country. Some have been incorporated into the main structure, or have become guest houses, pool houses, or storage spaces. He estimates that there are between fifty and 100 in Charleston alone.

“For African Americans who are interested in their genealogical past, it is personal. They take pride in knowing that these places still exist,” he says. “It is rare to be able to associate ancestry with a specific place because of the lack of records, but in many instances, descendants of the original property owners have stayed alongside those whose ancestors were enslaved. I didn’t go into this expecting a lot of the good things that have happened, but those are the kinds of relationships I get to build with this Project.”

At Magnolia Plantation, McGill says his mission is to ensure that the history and culture of all people who inhabited Magnolia will be disseminated through all interpretation at the site. This interpretation will exist in tours, signage, website, and social media. Tom Johnson, Magnolia’s executive director, says McGill is well-suited for this expanded position. “Joe has an enormous understanding of Magnolia and the history of the African-American experience in the United States,” Johnson said. “He has the sensitivity to help our guests understand the complexities of slavery and the impact it continues to have on and in our nation.”

“Now that I have the attention of the public by sleeping in extant slave dwellings, it is time to wake up and deliver the message that the people who lived in these structures were not a footnote in American history. We are living out that famous saying of Martin Luther King, Jr., ‘…one day the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit together at the table of brotherhood.’

“We are actually doing that. We’re putting those words into action, and that’s a good thing.”AM

For those interested in learning more about Magnolia Plantation and the Slave Dwelling Project, visit www.slavedwellingproject.org.

By Susan Frampton