Less than ten percent of the food eaten in South Carolina is grown within the state. GrowFood Carolina aims to change that.

It began as a vision from the executive director of the Coastal Conservation League, Dana Beach. Since founding the organization in 1989, Beach and his team have accomplished amazing things across the region, protecting millions of acres from overdevelopment. Beach imagined a future for the Lowcountry, a place consisting of a dense urban core surrounded by a flourishing greenbelt, protected from urban sprawl. The team at the Coastal Conservation League has worked tirelessly to head in the direction of such a vision, and while doing so, have identified many productive landscapes within the prospective and established greenbelt: family farms. In order for the farmed land to remain undeveloped by larger entities, the farmers have to keep growing, keep selling, and resist offers from real estate giants; a tall order for many rural families struggling to make ends meet. In 2007, the Coastal Conservation League decided to increase programs, and added, among other things, a focus on Food and Agriculture. During their information-gathering phase for this new program, team members from the Coastal Conservation League applied a grassroots effort to their work, visiting farmers and discussing the issues that threaten their ability to maintain their green, productive landscapes within the greenbelt surrounding Charleston. Time and again, the same issue came up: farmers often had trouble managing the gap between themselves and the community. The more digging the Coastal Conservation League did, the more they realized it came down to one thing: infrastructure. The farmers, toiling in their fields all day, simply did not have the time, money, or experience to market themselves and get consistently connected with restaurants, grocery stores, and institutions. They needed a bridge, so the Coastal Conservation League built it for them, establishing GrowFood Carolina that same year.

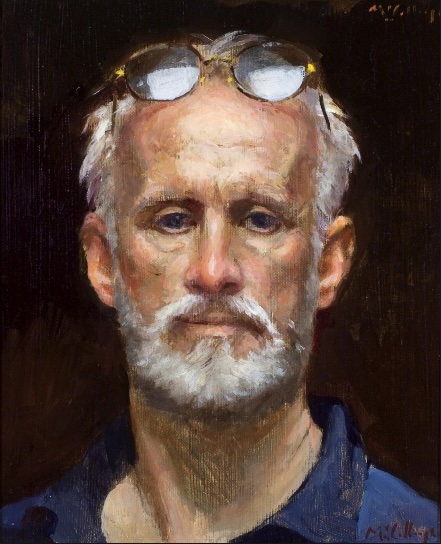

For a number of years, growth was slow and steady as the Coastal Conservation League tried to pin down exactly how GrowFood Carolina could operate most efficiently. In 2011, a longtime supporter of the Coastal Conservation League bought a building on Morrison Drive in Charleston and donated it, and GrowFood quickly moved in. The organization conducted a nationwide search for a person who truly embodied their mission, someone who could help create a powerful business plan. Enter Sara Clow, a New England-born former West Coaster who left her home in California to take the job with GrowFood. With the addition of the building and Sara Clow to the project, the impact of GrowFood Carolina has exploded, changing the landscape of food in the state more every day.

Under the leadership of Clow, GrowFood Carolina now operates as a food hub, a USDA-defined term that means, essentially, an organization that works to move local food products in efficient ways. At GrowFood, this translates into moving produce, dairy, nuts, salt, honey, and grains from the fields and farms to restaurants, retailers, and institutions.

“We look like a wholesale produce company on paper,” says Clow, “But we are really a service organization, especially for farmers. We bring the value back to the farmers and back to local food. We help the farmers maximize their acres and their profits so they can stay on their land, so their land is not used for improper development.”

Crucial to the organization’s mission is building a relationship with farmers, and the GrowFood team works with over 85 to date. They visit every one of the farms with which they work, getting to know the land, the workers, and the family. Regularly, they sit down with the farmers and have a crop production planning meeting, counseling them on the types and quantities of crops they should plant in order to maximize their profits in the coming seasons. Diversity is key, so the GrowFood team suggests variations on commonly grown produce. The result: instead of dozens of local growers trying to sell, for instance, yellow squash, some of them will grow zucchini, some will grow patty pan squash, and some will grow yellow squash according to the recommendations of GrowFood Carolina. In doing so, the value of the produce increases, and GrowFood is able to bring a wider array of products to the buyers.

When the time is right, GrowFood issues purchase orders to the farmers, and after harvest, the farmers, traveling from all over the state, deliver their crops to the warehouse on Morrison Drive. Everything is inspected and boxed up, and a sticker listing the name and location of the farm is affixed to each box before being stored in their coolers, aiding in single-source traceability and helping to build each farmer’s brand. All the while, the GrowFood team is working on sales, marketing, and preparing for distribution. Some of the product is presold, but most of the time, GrowFood sends availability lists to chefs and retailers, who then order what they’d like to feature that week. Their current distribution radius for their delivery vehicles is thirty miles, but they work with partners to get the produce and other goods to cities and states far beyond the limit. After loading up the trucks, the product gets delivered: some boxes will go to food trucks, while others will go to award-winning upscale restaurants downtown such as Husk. Some will make it into the hands of produce workers at grocery stores such as Whole Foods, Earth Fare, and Harris Teeter, while others will be handed to the cafeteria staff at the College of Charleston. At many of the destinations, the proprietors proudly list the farms from which they receive products, helping to place an emphasis on the value of locally produced items. The GrowFood team only keeps twenty percent of the sales revenues to keep up its operations; eighty percent is returned to the farmers.

Time and again, studies both scientific and anecdotal have shown that thriving local food systems are exceptionally beneficial to their communities. When fresh food grows locally, the personal health of the area’s citizens is measurably better than in food deserts. Farmers tend to be better stewards of the land in comparison to large developers and corporations, and lessening the number of miles food has to travel from farm to fork is always beneficial to the environment. Additionally, productive farms aid in the health of the rural economy, creating job opportunities in areas that may be struggling. Without a doubt, the efforts of GrowFood Carolina are overwhelmingly positive, and the organization has returned over 3.5 million dollars to small and mid-sized farmers across the state.

“We eat 11 billion dollars worth of food in South Carolina each year,” says Clow. “Less than ten percent of that is South Carolina-grown. For every percentage point we can increase that number, millions of dollars flow back into our economy. So a locally-grown tomato may be a few cents more expensive than a tomato picked green in another country, artificially ripened, and shipped in, but really, isn’t it worth it to put that money back into our communities, and into the pockets of these South Carolina farmers, some of the hardest working people you’ll ever meet? You can bet it’s more delicious.”

By Jana Riley