The lasting popularity of Charleston Receipts proves it to be more than a flash in the culinary pan, and for a new generation of cooks, it is the ultimate handbook to Lowcountry cuisine.

“The inheritance of a well-written recipe is as valuable as a silver spoon,” once wrote Heather Richie in Southern Living Magazine. In culinary currency, the 750 recipes compiled and tested by the sustaining members of Charleston’s Junior League in 1950 are a collection of shiny silverware that tells the story of life in the Lowcountry and transcends time.

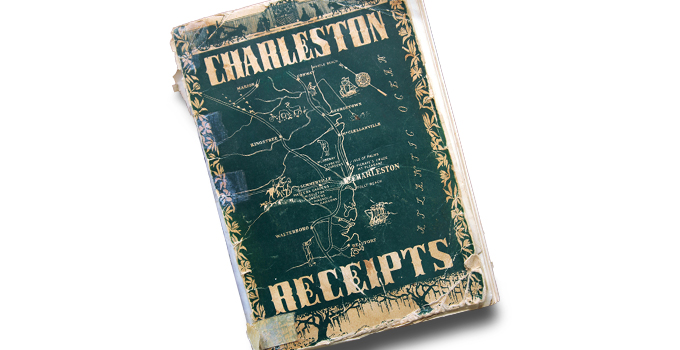

Alongside The Holy Bible, Charleston Receipts, the book referred to as “the Bible of all Junior League cookbooks,” has been named by many as most influential to the culture and cuisine of an area long heralded as unique. Though a relative newcomer by Biblical standards, Charleston Receipts has stood the test of time and proved that its relevance to life in the Lowcountry was far more than a flash in the pan.

Defining its contents as receipts in order to “designate time-honored dishes,” the organization’s cookbook committee set it apart from the outset. Each recipe was a voice of the Lowcountry, and represented far more than simply a list of ingredients and preparation instructions. Today, it is the oldest Junior League cookbook in print, and was inducted into the Walter S. McIlhenny Community Cookbooks Hall of Fame in 1990.

Whether your copy is brand new or passed to you by loving hands, listen closely and you will hear voices of those whose recipes are found on its pages, and of those who have treasured them through the years.

Talking With Tassie

A voice long silenced speaks from the pages of a worn cookbook, offering a glimpse of a remarkable woman.

Catharine “Tassie” Frampton was a woman seldom at a loss for words. A nurse and mother of three rambunctious boys, I am told that she was a pistol, and a force to be reckoned with. It saddens me that though my mother-in-law was an integral part of my life for the first few years of my marriage, she suffered a stroke that robbed her of speech long before we met. We never chatted over a bubbling pot, or talked over a rolling pin of the experiences that made her who she was.

But in the quiet of my kitchen, I have come to know her. From her tattered green and white cookbook, held together by crumbling brown masking tape, Tassie tells me about her life. She speaks of dinner parties and bridal showers, church socials and cotillions. Through spills and stains on dog-eared pages, she shares stories of family meals at the house on Summerville’s Main Street, of picnics at the lake and summer afternoons shrimping at Edisto.

Scraps of paper tucked here and there walk me through preparations for sweet treats and powerful punches. They offer solutions for a garden overflowing with vegetables, and tell me what to do with an excited boy’s catch of the day. The placement of her sister’s Oatmeal Raisin Cookie recipe, hand-written on the inside back cover, is an important sidebar to the conversation. Keep this recipe close at hand, she seems to say. Love is the unwritten but vital ingredient in every recipe.

Though its sound never fell on my ears while she was with us, when I need a recipe for shrimp, the Jerusalem artichokes are in season, or the figs are fat and brown on the tree, I know that I can turn to her beloved book, carefully turn the yellowed pages, and wait for Tassie’s voice to guide me—to tell me about her day, to talk to me about living in the Lowcountry, and to remind me that no matter what I’m cooking, to always remember the love.

By Susan Frampton