With a little help from their fellow soldiers, on Columbia’s Fort Jackson, a species has fought its way back from the edge of extinction.

There are several reasonable explanations for the persistent rat-tat-tat you might on Fort Jackson, the U.S. Army’s main production center for Basic Combat Training in Columbia, SC. Charged with providing trained, disciplined, motivated and physically fit warriors, Fort Jackson turns out over 48,000 basic training soldiers, and 12,000 additional advanced training soldiers every year. The sound could be target practice on one of the 100 ranges. Or a construction project on the 52,000 acres that also house the U.S. Army Soldier Support Institute, Armed Forces Army Chaplaincy Center, National Center for Credibility Assessment, and the Army’s Drill Sergeant Training School.

The last thing one might expect is that a small feathered creature is at the center of the ruckus – one that is hard at work on a new residence. But amidst the military installation’s training fields, rifle ranges, and 1,160 buildings, a rare bird species has taken up residence. In the comeback story of the century, the hard-working little army is setting records.

Once prolific, the Red-Cockaded Woodpecker population diminished by about 99% after Europeans settled in America. They dropped from around 1.6 million family groups to approximately 5,600, as 97% of the primary longleaf pine habitat system was lost to settlement, timber harvesting, urbanization, and agriculture. Officially labeled “endangered” in 1970, the birds came under the protection of the Endangered Species Act in 1973.

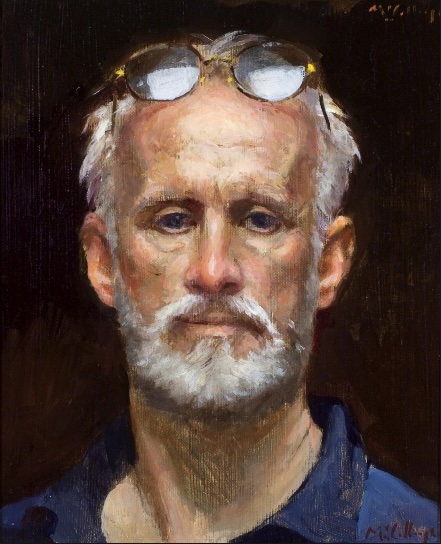

Territorial and non-migratory, the species is about the size of a cardinal. Its name is derived from a small red patch, or cockade, that the male wears on each side of its black cap. The pop of color stands out from the body’s horizontal black and white stripes. Homebuilding is serious business for the breeding male, and he is particular about the neighborhood he selects for his project.

While other woodpeckers bore out cavities in dead trees where the wood is rotten and soft, the red-cockaded woodpecker exclusively selects mature, living pine trees. Though it can take longer, cavity excavation takes one to six years. Additional cavities added to the original create a cluster for the species’ complex, cooperative social system, with family groups that consist of a breeding pair and up to four male (rarely female) offspring from previous years. These offspring, known as “helpers” assist in incubating eggs and brooding and feeding nestlings produced by the breeding pair.

The forests of Fort Jackson hold many coniferous woods but consist primarily of Longleaf Pine. Some Loblolly Pine and planted Slash Pine grow on upland sites with an understory of various Scrub Oak species. Wetland drains are dominated by Red Maple, Yellow Poplar, and other hardwoods. The areas managed for Red-cockaded Woodpeckers feature park-like conditions. Prescribed burning is done at regular intervals although a backlog of areas with no-burn histories remains. Some open spaces and fields are present, but most of the area is heavily forested, except the developed area at the western end of the Reservation.

Within this habitat, humans can replicate sites favorable for the woodpeckers’ homebuilding process. In 2007, the Army was tasked with helping to create habitats to aid in the recovery of the endangered species. It was a joint exercise that demanded cooperation from both human and feathered forces. Before the first breeding pairs could be released into the pines, trees were selected as home sites for the birds. The outer layer of bark of these trees was ground off, and sections cut out to make room for the placement of artificial cavities. Once in place, the man-made openings were covered with putty and paint to match the natural bark on the tree.

In 2015, Fort Jackson welcomed two pairs of the birds who carried on their tiny backs the hope of a new start for the species. Over 6,801 acres of the longleaf pine that is the Red-cockaded Woodpeckers’ preferred habitat has been restored. According to many measures, the 2018 nesting season was the best on the books, with the number of active clusters up by 7%, and the number of groups of trees with inhabited cavities up from 41 to 44. There were 41 potential breeding groups with at least one fertile male and female, with 37 reportedly attempted nesting. A new record of 150 eggs was laid, beating the previous record of 125, and more than 80 hatched.

Installation biologists use herbicides to convert some slash pine forests to longleaf pine forests and keep underbrush low to improve the bird’s habitats. On average, over the past five years, 11,819 acres have been burned on post annually, along with 2,388 thinned. Fire is essential to maintaining and restoring southern pine ecosystems, particularly the longleaf pine ecosystem, and is critical to red-cockaded woodpecker habitat maintenance and restoration.

With recovery plan guidelines calling for an annual average growth rate of 5% on all recovery populations, the industrious Red-cockaded Woodpeckers have met and exceeded the goal set for them. The rat-tat-tat that sounds in the forests of Fort Jackson is a welcome sound. The new homes being built and new families raised will help repopulate a species almost lost to South Carolina. The war has not quite yet been won, but the joint operation is an example of what is possible when an army of soldiers comes to the aid of a determined group of feathered fighters.

by Susan Frampton