The canvases of impressionist West Fraser are a tribute to the places he remembers and those we should never forget.

Though it might require one to be “of a certain age” to recall the melody, one need not be able to carry a tune to recognize the sentiment in the words of In My Life, a love song by Paul McCartney and John Lennon. “There are places I remember all my life, though some have changed. Some forever, not for better, some are gone, and some remain.” For those familiar with the art of impressionist West Fraser, the love song might be fitting prose to describe the collection of work in the artist’s repertoire. Fraser’s canvases are the places he remembers, from years spent exploring the woodlands, waterways, and marshes around Savannah to summering amidst the maritime forests and wetlands of Bluffton and Hilton Head Island. He intimately knows those that have been changed forever, are gone, or remain.

Born in Savannah, in 1964, his family permanently relocated to Hilton Head, where his uncle and father pioneered a new-concept development called Sea Pines. It was a move that transformed the coastal landscape of South Carolina and shaped the future of young Fraser, who watched it change the land around him. Fraser learned to appreciate the natural world and the freedom of plein air painting, a method referring to painting outdoors. Naturally artistic, he took note of the depth of the colors and the evolution of the light as it moved across the land. “I loved science, and I was always reading,” he recalls. “As I watched what was happening to the island where I grew up, I became really concerned about the environment. I knew from my early teens that I wanted to be a painter. I saw the changes coming, and it was disturbing. I knew I wanted to capture the wild places.”

A Fine Arts degree from the University of Georgia honed his artistic talent. He soon began his professional art career in watercolor. Though Fraser enjoyed great success as a watercolorist, the medium didn’t quite satisfy his creative vision. “I felt I’d gone as far as watercolor could take me.” “I stopped painting in watercolor and began working from photographs in the studio.” The new direction changed everything. He found that the heavy pigments of oil had been patiently waiting for his brush. “It is such a completely different medium,” he says of the transition. “It offered the rich colors I was looking for. I also found it easier and much more forgiving.” Today, his use of oils and his impressionistic style make his work instantly recognizable.

Fraser’s canvases reflect the immediacy of the moments, and his thick, loose brush strokes create subtle movement. Both method and style bring authenticity to the settings. For those who have walked in the sun-dappled hammocks of barrier islands or watched ribbons of sunlight shimmer in the gentle curve of a winding Lowcountry river, there is a familiarity. As though he has stood alongside us in places we ourselves remember, Fraser’s work reminds us of who we are and where we’ve been. His paintings are a passport to travel off the beaten path for those who have never been here.

But the natural landscape is not the only subject that draws the attention of his brush. “Charleston was hard to paint before Hurricane Hugo,” he says. “You couldn’t see it for all the crepe myrtles and other big trees blocking the buildings. The plein air movement was resurging about that time, and I wanted to get outside to capture the new views of Charleston the winds of the hurricane left exposed. I wanted to paint from life.”

In the unique perspectives he discovered, we are privy to bird’s-eye views of bright red rooftops, revealing steeples that rise against the skylines of Charleston and Savannah. In his rainswept streets, the ordinary is made extraordinary by the reflection of streetlights on glistening sidewalks. Colorful vignettes reveal Fraser’s affection for ordinary days at noonday crossroads and pocket-sized neighborhood shops. The work allows us brief moments in these places he remembers in his paintings and share the yearning for these places to remain.

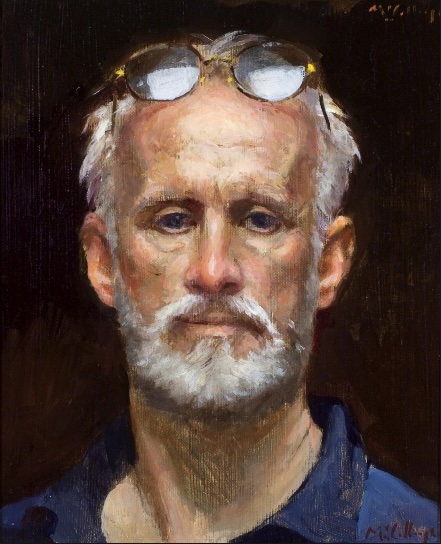

Fraser is also an accomplished portraitist and has famously chronicled three decades of The Heritage Golf Classic winners. Though forays into portraiture are relatively rare, these portraits hang in the hallowed halls of Harbor Town Links Clubhouse.

I was introduced to Fraser on a cobblestone street in the heart of Charleston. Through an oddly placed opening in an otherwise nondescript wall, he led the way down a brick-lined walkway to the unexpected urban grotto on the grounds of Charleston’s historic Confederate Home and College. Up the stairs, his studio is an enchanted space with soaring ceilings and drunken, tilting floors. Here, amidst glass-fronted cabinets filled with fossils and artifacts and tables laden with well-used brushes, West Fraser has spent over two decades producing a body of work garnering him national and international acclaim and a reputation as one of the best American painters of his time. Images of the Lowcountry’s most celebrated vistas and most intimate moments stand on paint-spattered easels and lean against water-stained walls. Like his surroundings, Fraser is warm and unpretentious, and one hears the Lowcountry’s cadence in his slow, measured speech.

“I began returning to the studio about five years ago because I started wanting to do larger paintings. It’s hard to do that in outdoor conditions that can rapidly change. More and more, I find myself painting from memory, sketching in the field, and returning to the studio to flesh out a larger canvas. Trudging through the mud and marsh with a 60 lb. backpack is a vigorous endeavor, and at some point, you can’t do as much of that,” he says, laughing at what he calls his “old age plan.” Many of his scenes are now composites of the thousands he has viewed in his lifetime.

Fraser feels fortunate to have had the safe harbor of the studio during the necessary social distancing of 2020. Unsurprisingly, under the circumstance, the serenity and natural beauty found in his images increased their demand. “It felt a little strange to be experiencing an uptick in business when so many were experiencing the opposite. But I think with people spending more time in their homes, many realized the importance of their surroundings reflecting the things they value—that bring a sense of peace to their world.”

Though he is currently working over the summer from his studio in a small Costa Rican village, the Lowcountry is never far from his thoughts. For this gifted son of the south, bringing to life the ever-changing palette of light and color is his way of paying tribute to the places he remembers. “I love to paint. It’s who I am. I hope that I have dutifully captured what I have seen in my life—so that we will all remember.”AM

By Susan Frampton