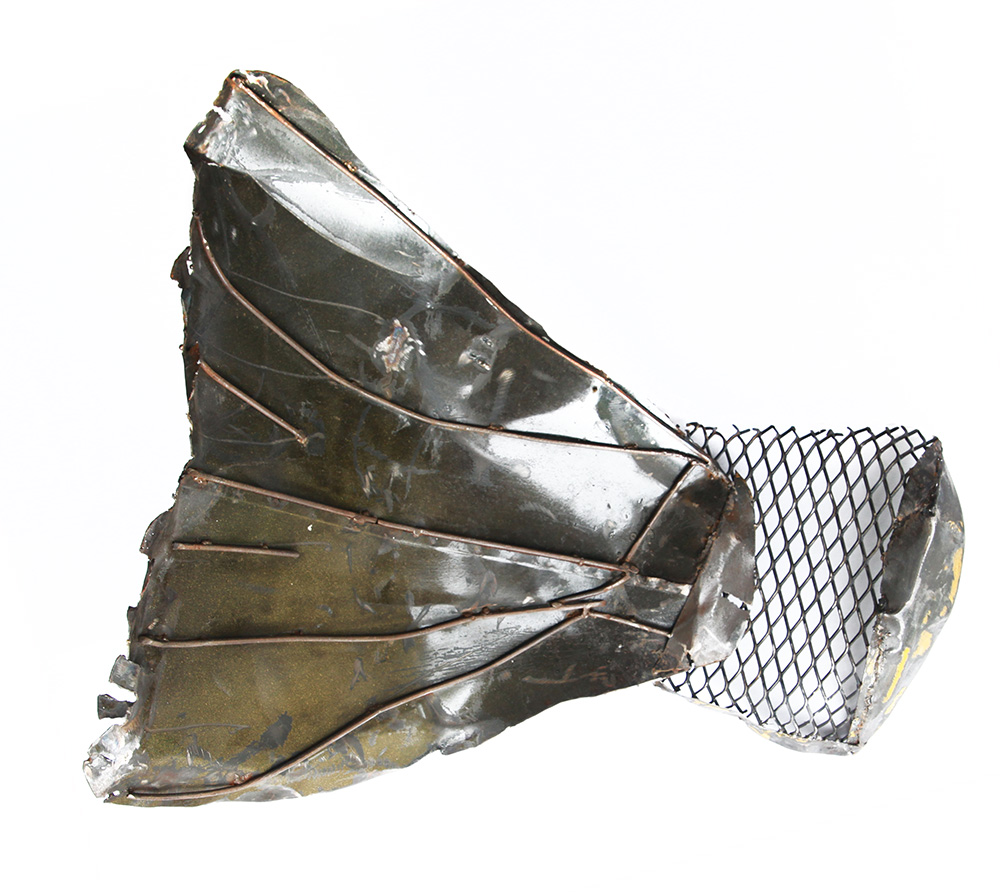

Using the tools of their trade, three monarchs of metal make art from the ordinary

Jason Elam

What’s in a name? Shakespeare says a rose by any other name smells just as sweet. But Shakespeare never met Jason Elam. He is an ironworker, and proud of it—so don’t call him a steelworker. There is a difference. Ironworkers work on bridges, structural steel, ornamental, architectural, and miscellaneous metals, on rebar and shops. Steelworkers manufacture or shape steel. That guy you see walking the six-inch girder high above the sidewalk? That ‘cowboy in the sky’ is an ironworker, aptly named for the way he rides a steel beam like a walk in the park.

From the time he was six years old, Elam looked for a way to get up off the ground and into the air. He built himself a helicopter from old bicycle sprockets and propellers to take him up. The project was not a success but made him even more determined to find a way to reach dizzying heights. The ironworking career path he chose provided the perfect vehicle to send him heavenward. He’s been up in the air ever since. Starting at the bottom of the well before working his way up, he learned mostly from experience. A proud member of The International Association of Bridge, Structural, Ornamental and Reinforcing Iron Workers Union, AFL-CIO (IW), Elam considers himself lucky to have learned from the best.

“I’m what they call a connector, the one that’s always way up there. I climb up there, and they fly the beams up to me. I connect them together.” It is a dangerous job that requires the agility of an acrobat and the strength of a lumberjack. They are skills that are in high demand, and his expertise keeps him on the road more than he’d like. “I’ve worked all across the country—Tennessee, Kentucky, Alabama, and Rhode Island. It’s really hard, being gone all the time,” says Elam of being away from Summerville and wife Adrienne. He also works locally on some of the Lowcountry’s most significant projects. I hung Boeing and Volvo, too,” he says of the high-profile jobs.

When he isn’t on the road, work in his commercial custom metalwork and welding shop, Rocky Steel keeps the ironworker plenty busy. He decided to have a little fun recycling and repurposing the scrap metal around the shop. There was no shortage of material to work with. “I’m the Fred Sanford of steel,” he says when his friends compare him to the notorious junkyard owner of television’s Sanford and Son. Transitioning to creating art from the pieces of scrap steel provides a welcome break from his high-flying job. Elam laughs at the contrast between the two. “I went from building America to building frogs.”

Like the man that makes a living walking in the sky, there is an underlying strength in his artwork. In many of his pieces, the power he applies to building skyscrapers is just below the surface, harnessed to fit the smaller scale. But in some, there is a whimsey that catches his audience by surprise.

Coming from the hardscrabble world of construction, Elam hasn’t gotten used to being referred to as an artist. The reception his work has received indicates that he’ll need to get used to it. “The first place I took it was the Night Market in downtown Charleston. It went really well, but after only two nights there, everything was shut down because of the virus.” It was a good start, so he began showing his work at the Jedburg Junction Farmer’s Market on Butternut Road. There, it has also found an appreciative audience. He hopes that at some point, he will be able to have work in both places.

“I’m an ironworker. But if folks want to call me an artist – I guess I’ll be an artist,” he says of his newly launched art career. Whether his days find him walking a steel beam, or sculpting the jagged scrap metal steel teeth of a shark’s jaw, the sky is clearly the limit for Jason Elam.

Shannon Reed

You can watch real housewives toss chardonnay and flip tables, or single guys pass out roses to vapid ingenues, but at the end of the hour, what have you really learned? However, if you’re looking for teachable television, you can find it on one of the small screen’s most riveting reality shows. One might not expect watching a handful of bladesmiths sweating over super-heated steel to provoke much excitement outside the cutlery drawer. But the History Channel’s Forged in Fire, which puts contestants through their paces to create a knife that is sharp, balanced, strong and suited for the task it is meant to perform, turns each episode into a real nail-biter. Over the hour-long show, we learn that creating the perfect knife requires patience, brains, brawn, and no small measure of artistic ability.

Shannon Reed, of Coastal Custom Knifeworks, has been approached several times by the show, but has resisted the lure of lights and cameras. The television contestants might get it done in an hour, he says, but there is no easy way of doing it, and no short cuts. “I’ve been doing it for ten years, and I’m still learning,” says the craftsman, whose designs can be found in specialty shops stretching from the Lowcountry to New England to Texas.

No stranger to working with his hands, Reed was looking for a hobby that would offer something he could share with friends and family. A plumber by trade, in his spare time, Reed built custom motorcycles from scratch and restored race cars, but it didn’t give him the satisfaction he was looking for. “I always liked working with metal, and I thought that I might like to try sculpting. I also really liked working with wood, but I knew I didn’t want to make furniture.” Introduced to the tradition and charm of Lowcountry oyster roasts by a family friend he greatly admired, Reed decided that he’d like to try his hand at making an oyster knife. That project offered the perfect combination of his interests. The special gift he made for his friend became the first of many. Far more than the mass-produced utilitarian knives he saw around him, Reed designed a functional work of art. Word spread, and requests for custom orders led him to launch Coastal Custom Knifeworks.

Squeezing out time to follow his passion isn’t easy for the 44-year-old craftsman. He’s dad to three rambunctious little boys, and a supervisor for Dorchester County Water and Sewer. His collection now includes a line of hunting knives, chef’s knives, and folding pocket knives. Created from both stainless and carbon steel, and from exotic and locally sourced materials, each style is customizable from blade to handle, with options such as a built-in bottle opener, leather sheath, or lanyard.

As beautiful as they are functional, Shannon Reed doesn’t want his knives to be treated as museum pieces —for display only. His designs have a reputation for being well-thought-out, balanced, comfortable to hold, and perfectly suited for their jobs. “Working with my hands, I have a real admiration for tools that last a lifetime. I don’t get offended, but it does upset me a little when people tell me that they’ll put them in a display case. That’s not what I want. I want them to be something customers enjoy using—that they’ll be able to hand down to their grandchildren.”

Reed says that he’s now turning toward creating slip joint folding knives, a traditional gentleman’s knife that is carried in the pocket. “I’m always surprised at how many people still carry pocketknives.” But like the classic story of the shoemaker whose children go barefoot, he rarely has one himself. “It never fails,” he says. “I’ll make something for myself, and I’ll try to hang onto it, but then somebody will call and say they need a knife for a gift, and they end up with mine.”

Pop some popcorn and give the tv show a look. Spoiler alert: you won’t find the Lowcountry bladesmith on reality television. He’s too busy working on his beautiful and functional designs. Forget the lights and cameras, as far as his customers are concerned, Shannon Reed is already a star.

Reed’s custom knives can be ordered at coastalknives.com or purchased locally at Summerville’s Four Green Fields or Hilton Head’s Skull Creek Boathouse.

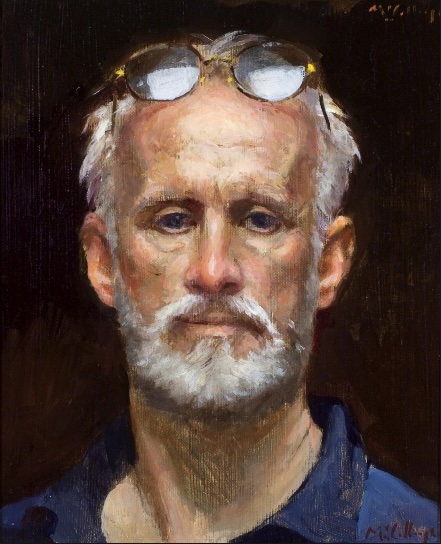

Brian McBride

Tell me what you’re looking for. Do you need someone to make you a cool sign for your business, bake you a cake worthy of a Cake Boss episode, or maybe to create a replica of a Taiwanese Navy ship? No? Sculpt you a horse with its mane flying in the wind, build you a one-of-a-kind dining table, or perhaps dismantle that tugboat or dredge you have lying around? No problem. I know a guy.

If you look up “Renaissance man” in the dictionary, it says a person with a broad range of interests that is an expert in several areas. If it’s an illustrated dictionary, you’ll find a photo of Brian McBride. Not really, but if they did that, he’d be the poster boy. McBride’s resume reads like a career catalog—marine salvage expert, woodworker, sculptor, and cake baker/decorator—and yes, I said cake. “I don’t do plumbing,” he says when asked to list what he isn’t good at.

“I’ve always just loved to create,” McBride says of what he does. When not running his Charleston-based marine salvage company, providing demolition and processing of both ferrous and non-ferrous material, McBride’s other interests allow him to explore that creative side. The brass, copper, and other metals he salvages provide the materials he works with as a metal sculptor. The imagination and creativity that turn it into art are all his. His avant-garde creations provided the impetus for Indigo East Gallery, the business he and his photographer wife, Dawn, owned and operated in Summerville.

Having no formal art background, McBride credits his grandfather for his interest in art. “That man had a gift like nothing I’ve ever seen. I’ve got his original India ink drawings and some of his carvings. He could take a piece of wood four feet tall and whittle at it until by the time he was done, he had a little three-foot-tall Pancho Villa with twin guns and chaps, all out of the wood. He just he was an amazing artist. He really was.”

Without McBride’s own eye for what lies within them, the scrap pieces of metal and slabs of wood he works with would remain just that. Regardless of the medium he chooses, each piece he creates is unique, whether crafted for sale at Nexton’s fine art gallery, Art on the Square, or commissioned. One of his favorite parts of commission-based pieces is reading between the lines to discover what the client is really looking for. “Sometimes you just have to intuit what they can’t exactly put into words. I take my cues from the lighting, the space it will go in, and even the client’s body language when describing what they want.” Nothing makes him happier than seeing the client’s face light up when their piece is revealed.

His subject matter varies from piece to piece, but the artist admits that nature provides him with the most inspiration. McBride’s artwork can be found in private collections throughout the country. One of his works, a replica of the Ravenel Bridge’s sail-like span, even found its way into a television show. “CBS Studios bought it. My wife recorded every single episode of the show, and we watched them in slow motion. She found it in two episodes.”

In unexpected contrast with the wood and heavy metal of his sculpture, McBride brings the same creativity to the medium of icing and fondant when baking and decorating cakes. Working with the sweet stuff isn’t such a stretch when he reveals that his mother and aunts operated a bakery. “I used to hang out in the back after school, making fondant flower petals.” Whether bringing exquisite detail to a wedding cake or capturing Oscar the Grouch’s exact expression in a three-tiered birthday cake, McBride’s cakes are works of art. “They taste good, too,” he laughs. As with his art, the clients’ reactions are the greatest reward. “That’s the fun of it, and I get that same feeling that I do when somebody sees my art for the first time.”

McBride looks forward to the day when creating art is his full-time job. “Marine salvage is a young man’s game.” Whatever renaissance he chooses for his future, you can be sure that Brian McBride will be just the man to get it done. AM

by Susan Frampton